Introduction:

Direct Stream Digital (DSD) has become a big thing in high-end digital audio. Simplified encoding and decoding, along with ultra-high sampling frequencies, promise unparalleled performance. Is this what we’ve all been waiting for or just mass-marketing hype? This blog separates the hype from the technical facts. I’ll explain in what ways DSD has the advantage and in what ways pulse-code modulation (PCM) is better.

If you're not sure if you should believe the statements in this blog which contradict much of the marketing hype, myth, and legend in the audiophile industry, feel free to check the references at the end of this blog.

You also may want to refer to my other blog on “The 24-Bit Delusion.”

A Brief History:

In 1857, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented the phonautograph, which could graphically record sound waves. In early 1877, Charles Cros devised a way to reverse that process on a photoengraving to form a groove which could be traced by a stylus, causing vibrations that could be passed on to a diaphragm, recreating sound waves.

In late 1877, Thomas Edison used Cros’ theories to invent the cylinder phonograph, allowing music lovers to experience recorded music in their homes for the first time. Can you imagine a modern cylinder phonograph? Tangential tracking…no arc error…no skating error. The concept was flawless.

In 1887, Emile Berliner invented the technically inferior disk phonograph. Disks warp and there was arch error and skating errors introduced. Certainly no comparison to the tangential tracking Edison cylinder player.

But since disks are much cheaper to produce than cylinders, and since disk fit nicely in display bins at stores and can include larger cover art and notes, they became the standard. And so began the long history of the recorded music industry being more about consumer convenience and optimal profits than about optimal fidelity.

The digital revolution was no different. Philips and Sony collaborated on the new standard for a consumer digital format in 1979. Philips wanted a 20 cm disk, but Sony insisted on a 12 cm disk which could be played in a smaller portable device. In 1980 they published the Red Book CD-DA standard, and mass-market digital music was born. Many in the recording industry in the early days of digital joked that CD stood for “compromised disk.”

In the early 1980s, when digital recording became readily available, studios converted from analog to digital to save money. For studios, this cost less for the equipment, required less space for both recording and archiving, and made it easier to mix and edit tracks in post-production. For consumers, there weren't many advantages. Most of the early digital recordings were produced with relatively low resolution and sounded so fatiguing they would make you want to tear your ears off.

The switch from PCM to DSD was no different. In the early 1990s Sony wanted a future-proof, less expensive medium to archive their analog masters. In 1995 they concluded that storing a 1-bit signal directly from analog-to-digital would allow them to output to any conceivable consumer digital format (LOL...later I'll explain how Sony screwed the pooch on this decision). This new 1-bit technology was achieved by outputting from the monitoring pin on Crystal’s new 1-bit 2.8Mhz Bit Stream DAC chip.

Later, Sony’s consumer division caught wind of DSD and collaborated with Philips to create the SACD format. Of course, from the time the SACD was conceived until the time it came to market, DAC chip manufacturers had advanced from 64fs to a higher 128fs sampling rate (aka Double-Rate DSD) and from 1-bit to a higher-resolution 5-bit wide-DSD format. If the SACD format was DSD128 instead of DSD64 and 5-bits instead of 1-bit it would have made a huge difference in performance. Oops.

Long before the DVD, SACD, or DSD formats were developed, the Bit Stream DAC chip was introduced to the consumer market as a lower-cost alternative to the significantly more expensive R-2R multi-bit DAC chip. Bit Stream DAC chips have built-in algorithms to convert PCM input to DSD, which is then converted to analog. Once again, the result was a huge cost saving at the expense of fidelity.

It was in part Bit Stream DAC technology which allowed the development of our modern 7.1 channel audio that’s embedded into video formats. This also allowed electronics manufacturers to market DVD players in small chassis with cheap power supplies which could retail for under $70. Once again, the audio purist never stood a chance.

In contrast, not only do multi-bit R-2R DAC chips cost significantly more to manufacture than single-bit DAC chips, but they also require much larger and more sophisticated power supplies. If you were to make a 7.1 channel R-2R multi-disk player, it would cost several times the price of Bit Stream technology and it would be several times the size. Certainly not what the average consumer is looking for.

To sum things up, the recorded music industry has made decision after decision to maximize profits and mass consumer appeal at the expense of the audio purist. History lesson over.

DSD vs. PCM Technology:

PCM recordings are commercially available in 16-bit or 24-bit and in several sampling rates from 44.1KHz up to 192KHz. The most common format is the Red Book CD with 16-bits sampled at 44.1KHz. DSD recordings are commercially available in 1-bit with a sample rate of 2.8224MHz. This format is used for SACD and is also known as DSD64 or single-rate DSD.

There are more modern, higher-resolution 1-bit DSD formats, such as DSD128, DSD256, and DSD512 as well as wide-DSD formats with 5-bit to 8-bit Delta-Sigma decoding which I will explain later. These formats were created for recording studios and comprise only a very small portion of the recordings which are commercially available.

Though you can’t make a direct comparison between the resolution of DSD and PCM, various experts have tried. One estimate is that a 1-bit 2.8224MHz DSD64 SACD has similar resolution to a 20-bit 96KHz PCM. Another estimate is that a 1-bit 2.8224MHz DSD64 SACD is equal to 20-bit 141.12KHz PCM or 24-bit 117.6KHz PCM.

In other words a DSD64 SACD has much higher resolution than a 16-bit 44.1KHz Red Book CD, roughly the same resolution as 24-bit 88.2KHz PCM recording, and not as much resolution as a 24-bit 176.4KHz PCM recording.

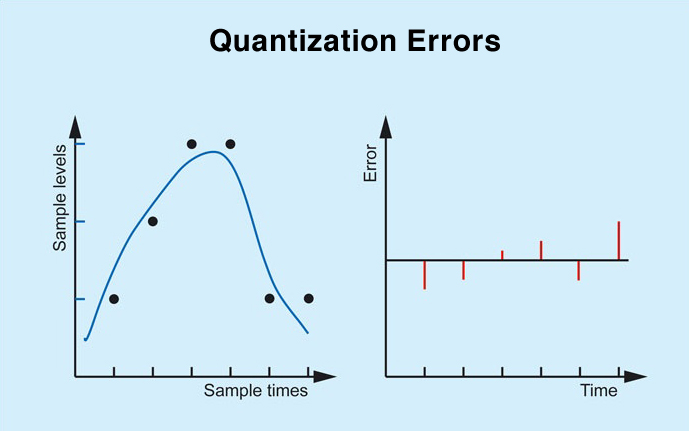

Both DSD and PCM are “quantized,” meaning numeric values are set to approximate the analog signal. Both DSD and PCM have quantization errors. Both DSD and PCM have linearity errors. And both DSD and PCM have quantization noise that requires filtering at the output stage. In other words, neither one is perfect.

PCM encodes the amplitude of the analog signal sampled at uniform intervals (sort of like graph paper), and each sample is quantized to the nearest value within a range of digital steps. The range of steps is based on the bit depth of the recording. A 16-bit recording has 65,536 steps, a 20-bit recording has 1,048,576 steps, and a 24-bit recording has 16,777,216 steps.

The more bits and/or the higher the sampling rate used in quantization, the higher the theoretical resolution. So a 16-bit 44.1KHz Red Book CD has 28,901,376 sampling points each second (44,100 x 65,536). And a 24-bit 192KHz recording has 32,212,254,000,000 sampling points each second (192,000 x 16,777,216). This means 24-bit 192KHz recordings have over 111,455 times the theoretical resolution of a 16-bit 44.1KHz recording. No small difference.

So why is it that HD recordings sound only slightly better than a 16-bit 44.1KHz recordings made from identical masters? Later in this blog I’ll explain the difference between theoretical and actual resolution.

DSD encodes music using pulse-density modulation, a sequence of single-bit values at a sampling rate of 2.8224MHz. This translates to 64 times the Red Book CD sampling rate of 44.1KHz, but at only one 32,768th of its 16-bit resolution.

In the above graphical representation of PCM as a dual axis quantization, and DSD as a single axis quantization, you can see why the accuracy of DSD reproduction is so much more dependent on the accuracy of the clock than PCM. Of course, the accuracy of the voltage of each bit is just as important in DSD as PCM, so the regulation of the reference voltage is equally important in both types of converters.

Of course the accuracy of the clocking during the recording process which is done at several times the resolution of commercial DSD64 SACD and 16-bit 44.1KHz PCM recordings is significantly more important than the accuracy of the clocking of either DSD or PCM during playback.

There are other DSD formats which use higher sampling rates, such as DSD128 (aka Double-Rate DSD), with a sampling rate of 5.6448MHz; DSD256 (aka Quad-Rate DSD), with a sampling rate of 11.2896MHz; and DSD512 (aka Octuple-Rate DSD), with a sampling rate of 22.5792MHz. And most modern A to D and D to A Delta-Sigma converters do multibit wide-DSD with 5-bits to 8-bits decoding in parallel. All of these higher-resolution DSD formats were intended for studio use as opposed to consumer use, though there are some obscure companies selling recordings in these formats.

Note that Double, Quad, and Octuple DSD have both the potential for a 44.1KHz multiple and a 48KHz multiple sample rate for 100% equal division down to DSD64 SACD and 44.1KHz Red Book (both 44.1KHz multiples) or 96KHz and 192KHz High-Definition PCM formats (both 48KHz multiples).

Of course when studios convert a 48KHz multiple format to a 44.1KHz multiple format or visa versa they introduce quantization errors. Sadly this is often the case with older recordings when they are released in a remastered 24-bit 192KHz HD version derived from DSD64 masters, such as the ones Sony and other companies used to archive their analog masters in the mid-90's. Note that the optimal HD PCM format which can be created from a DSD64 master would be 24-bit 88.2KHz. Any sampling rate over 88.2KHz or that is equally divisible by 48KHz would have to be interpolated (not good). But consumers demand 24-bit 192KHz versions of all their old favorites, so companies provide them, despite the known consequences.

The Problems:

There are three major areas where both PCM and DSD fall short of perfection: quantization errors, quantization noise, and non-linearity.

Quantization errors can occur in several ways. One way which was most common in the early days of digital recording had to do with the resolution being too low. Think of the intersection points on a piece of graph paper. You can’t quantize to a fraction of a bit, and you can’t quantize to a fraction of a sampling rate. You can only quantize to a value which falls on the intersection points of bit-depth and sampling rate. When the value of the analog signal falls between two quantization values, the digital recording ends up recreating the sound lower or higher in volume and/or slower or faster in frequency, distorting the time, tune, and amplitude of the original music. Often this creates unnatural, odd harmonics which result in the hard, fatiguing sound associated with early digital recordings. Note on the graphic below that the solid blue line represents the actual music wave and the black dots represent the closest quantization values.

Though modern sampling rates are high enough to fool the human ear, quantization errors still occur when translating from one format to another. For example, when Sony decided to archive their analog master libraries to DSD64 back in 1995, they were wrong to believe that these masters would be future-proof and able to reproduce any consumer format. The fact is, these masters could only properly reproduce a format that was divisible by 44.1KHz. So any modern 96KHz or 192KHz recording created from DSD64 master files have quantization errors.

This leads me to one of the many things that enrage me about the recorded entertainment industry. If 44.1KHz was the standard which was engineered to put aliasing errors in less critical audio frequencies, then why did they start using multiples of 48KHz?!?!?!? All they had to do was go with 88.2KHz and 176.4KHz as the modern HD consumer formats, and all of this mess could have been avoided. They made DXD, a 24-bit 352.8KHz studio format, equally divisible by 44.1KHz. What blithering idiot decided to put a wrench in the works with 96KHz and 192KHz HD audio?!?!?!?

The actual reason for the 48KHz multiple has to do with optimal synchronizing to video. So it makes sense to have sound tracks from movies recorded in a 48KHz multiple, such as the 24-bit 96KHz format embedded into 7.1 channel audio on DVDs and Blu-Rays. But since over 90% of all music recordings are sold in a 44.1KHz for Red Book CD or DSD64 SACD it is rather ridiculous to offer any HD music in 96KHz or 192KHz as opposed to the optimal 88.2KHz and 176.4KHz HD formats. But because naive consumers wrongly believe that the higher the sampling rate the higher the fidelity they demand 192Khz falsely believing it is better than 176.4KHz, so that is what record companies market.

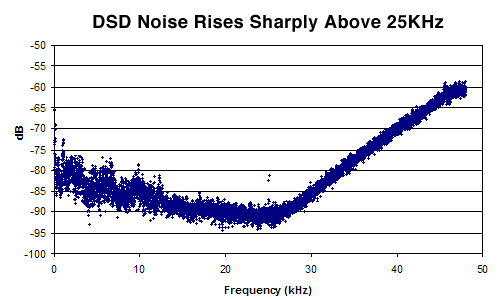

Quantization noise is unavoidable. No matter what format you digitize in, ultrasonic artifacts are created. The more bits you have, the lower the noise floor. Noise floor is lowered by roughly 6db for each bit. So as you can imagine, 1-bit DSD has significantly more ultrasonic noise than even 16-bit PCM. This is part of why wide-DSD formats with 5-bit to 8-bit parallel Delta-Sigma decoding were created. With PCM, you have to deal with significant noise at the sampling frequency. This is why Sony and Philips engineered the Red Book CD to sample at 44.1KHz, which is over twice the human high-frequency hearing limit of 20KHz.

Since quantization noise is present around the sampling frequency of a PCM recording, a 44.1KHz recording has quantization noise one octave above the human hearing limit of 20KHz. This quantization noise needs to be filtered out, so all DACs have a low-pass filter at the output. Because the quantization noise is only one octave above audibility the filters used have a very steep slope so as to not filter out desirable high frequencies. These steeply sloped low-pass digital filters are commonly known as "brick wall" filters. This is why there can be an advantage in playing 44.1KHz PCM upsampled to 88.2KHz or 176.4KHz.

Though you hear a lot about "brick wall" filters causing an audible distortion in the top end of early Red Book CD players , the fact is that was only a small part of the reason early Red Book CDs and players had an unnatural sounding top end. Most of the hard, harsh, unnatural sounding high frequencies in early digital had more to do with flaws in the power supplies and flaws in the recording process, not "brick wall" filters.

Sorry to be the one to burst your bubble, but despite what many audiophiles may believe, less than one person in a thousand can hear anything above 20KHz as a child and there is almost no one over the age of 40 who can hear much above 15KHz.

Of course DSD64 is another story: above 25KHz the quantization noise rises sharply, requiring far more sophisticated filters and/or noise-shaping algorithms. See graphic below. When you filter the output of DSD64 with a simple low-pass filter, the result is distorted phase/time and some rather nasty artifacts in the audible range. The solution is noise-shaping algorithms which move the noise to less audible frequencies and/or higher sampling rates. This is why Double-Rate DSD and Quad-Rate DSD formats came into being. This is also why advanced player software, such as JRiver, offers Double-Rate DSD output. Using player software that upsamples DSD64 to DSD128 or DSD256 significantly improves performance by putting the digital artifacts octaves above audibility allowing more advanced noise-shaping algorithms and less severe digital filters. Note these extremely high sampling frequencies are why ultra accurate clocking is more important in the playback of DSD than PCM recordings.

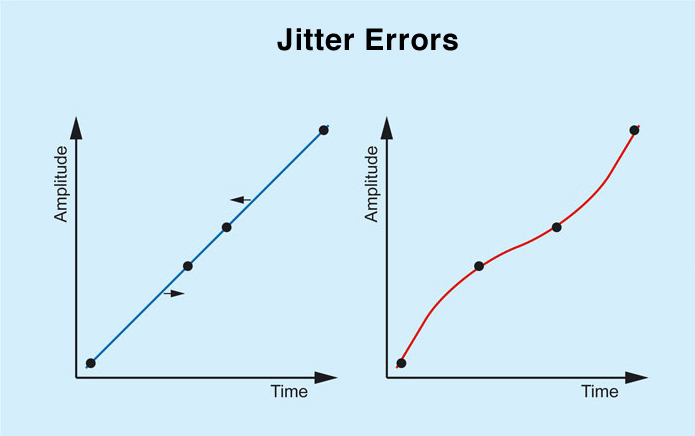

Jitter is defined as inconsistencies in playback frequency caused by inaccurate clocking. The result is observable as distortion of the time and tune of the music. Often the pattern of the inconsistency of frequency can result in an analog wave form that has an unnatural odd harmonic frequency. This results in the fatiguing character commonly known as “digititis.” Note in the two graphs below: jitter is an inconsistency in the horizontal time axis and non-linearity is an inconsistency in the vertical amplitude axis.

Jitter occurs when the converter’s clock rate is inconsistent and non-linearity can occur when the converter's reference voltage is inconsistent. This is why we are hearing so much about “super clocks” and “femto clocks.” The more accurate the clock, the more accurate the analog output. This is also why ultrahigh-performance R-2R DACs, such as Mojo Audio’s Mystique, have a way to adjust the voltage of the most-significant-bit (MSB) at the zero crossing to optimize linearity.

The Myth of Pure DSD:

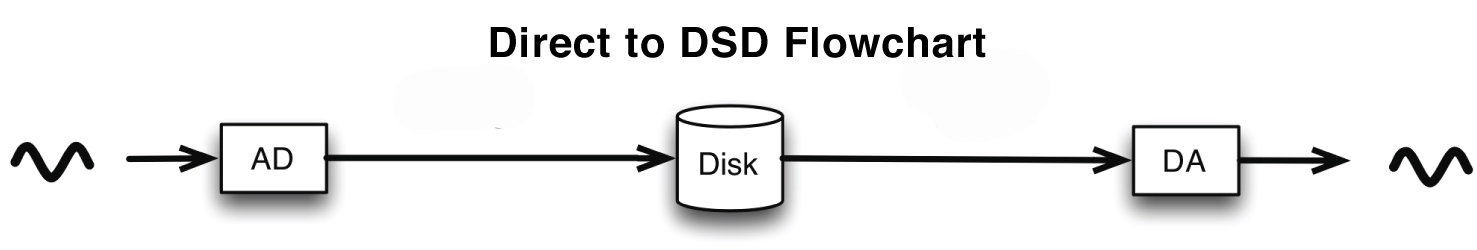

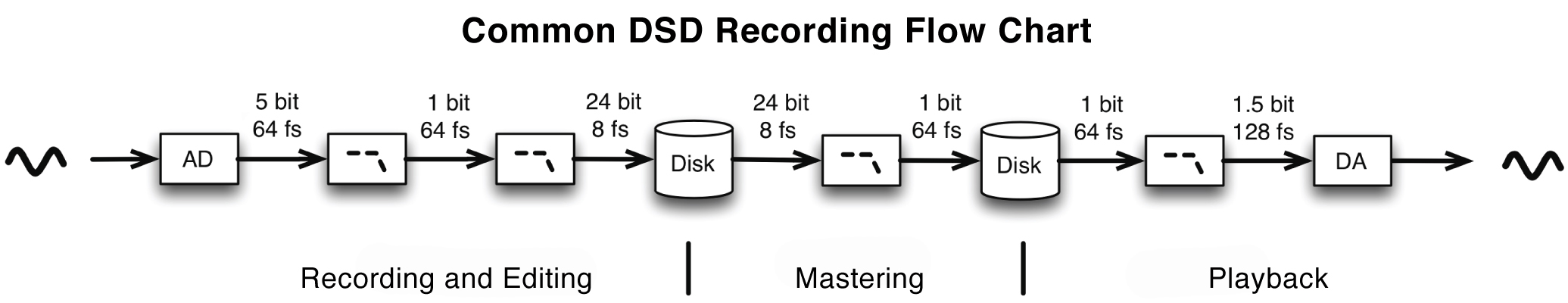

Despite the marketing hype, there are almost no pure DSD recordings available to consumers. This is partially because up until quite recently there was no way to edit, mix, and master DSD files. So most pure DSD recordings which are commercially available are those recorded direct to DSD without any post-production. There are some new studio software packages which can edit, mix, and master in DSD, but these are quite rare in the industry, and mostly used by small boutique recording companies. Most DSD recordings are in fact, edited, mixed, and mastered in PCM and then converted back to DSD. The marketing hype DSD flow chart you see below rarely exists anywhere but in theory. Yikes…the secret is out.

There are several generations and levels of quality in purely digital DSD recordings. The least pure are DSD recordings made from old PCM masters. Many of these PCM masters had low resolution as well as significantly higher quantization errors and lower linearity than modern PCM recordings. Since you can never get better than the original masters, these DSD recordings sound as bad as or worse than the original low-resolution PCM masters. The purest common DSD recordings come from modern DSD masters which are recorded in 5-bit to 8-bit Wide-DSD, which is in fact a 5-bit to 8-bit parallel Delta-Sigma encoding.

As you can see from the above flow chart, most commercially available DSD recordings have to be converted back and forth to a PCM format in order to do post-production editing, mixing, and mastering. In each of these conversions, more quantization noise and/or quantization errors are added to the recording. For that reason they created these inaudible resolution 24-bit and Wide-DSD formats with insanely high sampling rates. The higher the resolution during editing, mixing, and mastering, the lower the digital noise in the audible spectrum when these recordings are downsampled to commercially available formats.

It is quite unlikely that any or many of recording studios that are currently using Wide-DSD for editing, mixing, and mastering will ever upgrade to software that can edit, mix, and master in true DSD, since DSD is in fact an obsolete format. Even Sony no longer supports DSD and SACD. The modern format which recording studios will likely be upgrading to would be MQA, which compresses much better than DSD or PCM for streaming and decodes to PCM formats, such as 24-bit 88.2KHz. That is why HD music streaming services such as Qobuz and Tidal are switching over to MQA for their ultra-HD selections. So with the invention of MQA compression, PCM is quickly becoming the preferred HD music format.

Another common marketing myth about DSD vs. PCM is that when blind listening tests were done comparing DSD to PCM, there was a consensus that PCM had a fatiguing quality and DSD had a more analog-like quality. This was proved to be total marketing BS. One way that marketing lie was perpetuated was with hybrid SACDs which have DSD64 and 16-bit 44.1KHz PCM on the same disk. The DSD64 tracks have over 30 times the resolution of the 16-bit 44.1KHz tracks so that they could make DSD sound better than PCM in comparisons. The truth is that in recent blind studies they've proved that high-resolution PCM and DSD are statistically indistinguishable from one another. Considering that nearly all DSD recordings were edited, mixed, and mastered in PCM, it is no wonder.

Then there are the differences in the ways DAC chips work. Most modern DAC chips are Delta-Sigma which decode native DSD. R-2R DAC chips decode native PCM. In order for you to play PCM files on a Delta-Sigma DAC or DSD files on an R-2R DAC the files have to be converted in real time.

Most modern Delta-Sigma DAC chips can decode multiple file formats, including PCM, DSD, and Wide-DSD. When they are decoding PCM, a Delta-Sigma DAC chip has to first convert it into DSD, the chip's native format. Another reason for the common misconception that DSD performs better than PCM has to do with the poor quality of the real-time PCM to DSD converters built into native DSD Delta-Sigma DACs. Since R-2R ladder DAC chips can only decode PCM formats some DAC manufacturers use chips or FPGAs at the input stages of their DACs which convert DSD to PCM. But no R-2R DAC chip can decode DSD on its own.

In almost all cases I would recommend playing music files in the native format which your DAC chip decodes. That would be PCM for an R-2R DAC chip and DSD for a Delta-Sigma DAC chip. There are several brands of player software on the market which have real-time PCM to Double-Rate DSD converters. HQ Player is one of the most sophisticated player software packages on the market today. HQ Player can be configured for real-time PCM to DSD conversion as well as real-time DSD upsampling to Double, Quad, Octuple, and even higher rate DSD formats. Using player software that is capable of converting PCM to DSD and upsampling it to at least Quad-Rate DSD is highly recommended.

Summary:

Well, all that’s a real ear opener, isn’t it?

When people claim to hear significant differences between PCM and DSD it is not the difference between the formats that they are hearing, but most often the difference in the quality of the digital remastering or the native format their specific DAC decodes. Delta-Sigma DACs decode native DSD and R-2R DACs decode native PCM.

Keep in mind that most recordings are engineered to sound best on a car stereo or portable device as opposed to on a high-end audiophile system. It’s a well-known fact that artists and producers will often listen to tracks on an MP3 player or car stereo before approving the final mix.

The quality of the recording plays a far more significant role than the format or resolution it is distributed in. But to increase profits, many modern recording studio executives insist that errors be edited out in post-production, significantly compromising the quality of the original master tapes. So no matter what format these recordings are released in, the music will always sound mediocre, since you can never have higher performance than what is on the original masters.

In contrast, some of my favorite digital recordings were digitally mastered from 1950s analog recordings. Many of these recordings were done as a group of musicians playing in a room with one take per track and no post-production editing. Though these recordings have much higher background noise being limited by old-school pre-Dolby 60dB dynamic range master tape, they retain an organic character and in-the-room harmonic cues that can't be duplicated any other way.

Hear It for Yourself:

Are you curious about the potential of digital-to-analog conversion?

Mojo Audio’s Mystique EVO DAC has the purest digital conversion possible.

- A true non-oversampling R-2R ladder DAC design.

- No noise-shaping, upsampling, or oversampling algorithms.

- MSB zero-crossing voltage adjustment circuitry to optimize linearity.

- Perfectly bit-aligned left and right channel hardware-based demultiplexing.

- Direct-coupled with no output capacitors or transformers to distort phase and time or narrow bandwidth.

- LC choke-input power supplies, which unlike capacitive power supplies, store both current and voltage.

The Mystique is in a class by itself. Explosive micro-dynamics combined with harmonically coherent micro-details reveal the true time, tune, tone, and timbre of the original musical performance.

With Mojo Audio’s 45-day no-risk audition you can hear the Mystique DAC for yourself, in your own system, with no-risk and no restocking fees. Experience all the harmonic coherency and emotional content digital music is capable of delivering.

If you like what you've read in this blog and are interested in getting more free tips and tricks, check out the rest of my blogs on our website. Also, sign up for our e-newsletter to get more useful info as well as discount coupons, special offers, and first looks at new products.

Enjoy!

Benjamin Zwickel

Owner, Mojo Audio

Source: https://www.mojo-audio.com/blog/dsd-vs-pcm-myth-vs-truth/