You know the place I’m talking about. If you’ve watched Seinfeld, it’s the diner Jerry and friends hole up in almost every episode, but that’s wasn’t why I was there. This was where Suzanne Vega wrote her song “Tom’s Diner” sometime in 1981. Now I’m not the biggest Suzanne Vega fan, but there’s a reason she’s considered the mother of MP3. “Tom’s Diner” was used extensively in the research that went into the creation of the MP3 format. And this diner is where it all began.

It’s a good song, but more importantly, it’s entirely a cappella—and recorded flawlessly. Audiophiles in the late 80s found that the smooth yet subtle performance Vega delivered in the original was perfect for tuning their hi-fi speaker systems. As it turns out, the human voice was a good way to test for clarity, and playing “Tom’s Diner” reveals minor tuning problems in a speaker.

But as most great things in life are, Tom’s Diner’s historical importance happened completely by chance. Karlheinz Brandenburg (the lead scientist working on the compression algorithm) was finishing up his post-doctorate working on digital music compression, when he heard “Tom’s Diner” playing on the radio down the hall. “This. This is the song that I will listen to countless times on my mission to create the best audio algorithm the world has ever seen!”, he thought to himself. And yes, I did make that part up but every hero (or villain) needs that eureka moment so I took some liberties here. Anyway, back to the story.

Brandenburg had been studying psychoacoustics, or how people perceive music, and used the concept of auditory masking as the baseline for what he wanted his algorithm to do. Without getting too scientific, auditory masking is when there is a loud sound that drowns out another smaller sound.

For whom the bell tolls

If I strike a bell in a quiet room, and then go outside and strike it again, listen to what happens.The bell didn’t sound the same just then, did it? It was harder to hear, lost in the cacophony of the outside world. The ringing was shorter, wasn’t it? Also, was the bell quieter? It was.

No, the outside world didn’t make that bell sound any different, but rather, the way MP3 compresses audio did. But even if you tried this for yourself in the real world, the result would be similar. Our ears and brain didn’t evolve to hear the difference between two specific tones at 632Hz and 635Hz, they evolved to hear a growl. Or a yell. You know, sounds that might signal impending doom.

If a louder sound of similar frequency is present with a quieter one, your brain deletes it. This physiological response—auditory masking—is the entire basis of the psychoacoustic algorithm that defines MP3 compression. Any sound your brain would normally not be able to hear: the encoding deletes to save space. If it works as intended, you’ll have a much smaller file- and your ears would be none the wiser. This happens all the time in our everyday lives. Ever been in a bar that’s too loud to hear what your friend is saying? Same thing.

Brandenburg used this to his advantage, devising an algorithm that would find the sound data that humans couldn’t hear because of auditory masking, and just getting rid of it. He took “Tom’s Diner” and ran it through his compression algorithm…. and Vega’s vocals in “Tom’s Diner” sounded like a possessed demon fighting its way through his speakers. Clearly, the algorithm was doing something funky. So he tweaked it, and ran it again. And again. And again. Each time changing the algorithm slightly until, after what I’m sure was a great few months of listening to the same song constantly, the differences between the original and the end result were almost imperceptible. MP3 compression was finally ready for the big time.

When the MP3 was invented, it was still a long way off from becoming the dominant music format of the new millennium. It had to overcome technological limitations, a cartel-like recording industry, and it needed the internet to do it.

While MP3 was a great way to compress an audio file in 1990, consumer storage just wasn’t up to the task. While you could theoretically hold 700MB on a CD, hard drives of the time were typically no bigger than a few tens of megabytes at best. You couldn’t just copy 700MB of uncompressed WAV audio- there just wasn’t space. Piracy wasn’t really a viable option.

At the time, if you wanted digital audio, you had to go to record store… or sign up for one of those insane CD clubs. You couldn’t listen to songs before buying them without the radio. You couldn’t just go on YouTube, and you definitely couldn’t torrent anything on a dial-up modem. The music industry knew it had a monopoly on its market, and from 1995 through 2000, several companies banded together to artificially inflate the price of CDs by about $5 per album. Consumers knew they were getting gouged, but there wasn’t a clearly superior alternative until 1999. That year, all hell broke loose, and MP3 began its ascent to becoming the dominant music format.

Evolution

The world of 1999 was far different than the world of 1990. Hard drive storage had climbed orders of magnitude greater from 20MB into several Gigabytes of storage. 56k and cable modems were replacing the 24-baud models of the past, allowing just enough download speed to snag an MP3 in a few minutes, and just like that: the landscape was fertile for MP3’s technological revolution.That revolution came in the form of Napster. Founded in the greater Boston area by brothers Shawn and John Fanning; along with Sean Parker, Napster offered its users a peer-to-peer networking solution to share their music online. For the first time ever, your average consumer could go online, search for anything they wanted, download it, and create a library of digital music without buying anything. CD-Rs allowed users to create their own CDs as well. Piracy wasn’t just an expression of rebellion, but a market response to an overpriced and inflexible commodity.

By early 2000, Napster had over 20 million users, downloading over a billion songs. By former employees’ own accounts, their software team could barely keep up with how fast the traffic expanded, even after attracting significant resources from venture capital firms to address the issue.

That was the first sign that file sharing wasn’t just a flash in the pan. It was here to stay. In fact, the number of P2P file sharers would continue to expand, with the NPD group estimated 15 million households used P2P networks in 2006, and 18.3% of all computers worldwide had Limewire (another popular P2P service) installed.

Almost 20 percent of the world's computers had Limewire. That's more than had macOS. Let that sink in.After a 31% drop in industry CD sales that year, the Recording Industry Association of America, or RIAA panicked, and found an opportune punching bag in online music piracy. Though the MP3’s spread arguably increased demand for music, they tried to strangle it in the crib by suing Napster.

The future of the popular file sharing service became the hot-button issue of 2000, with musicians and record companies alike taking starkly diverging positions on the issue in a very public forum. Many people remember the outspoken Lars Ulrich of Metallica fame leading the RIAA’s crusade against Napster, but fewer people remember Public Enemy frontman Chuck D’s oddly prescient defense of free music sharing in a debate between the two musicians hosted by Charlie Rose.

Chuck’s position was that MP3 sharing was going to change the balance of power in favor of the content creator, instead of the record label holding all the power. While Lars claimed that it didn’t matter: MP3 sharing was (in his words) illegal, Chuck pointed out that most people across the globe didn’t have a way to “get found” and that distributing music for free online would increase demand.

History proved Chuck D right, but unfortunately for Napster, they lost their fight and shut down in July 2001. But the toothpaste was out of the tube. As soon as one P2P service was destroyed, another cropped up, and so on and so forth over the 2000s. When attacking P2P services didn’t stem the tide of MP3 sharing, he RIAA went after thousands of individuals by abusing the subpoena process, famously attempting to sue twelve-year-old children and the people who were literally incapable of stealing the music they were sued over. In most of the 17,587 people sued, the RIAA opted to take a cash settlement instead of pursuing cases to completion, but the industry’s image was tarnished forever as a result.

And MP3 sharing persisted.

New horizons

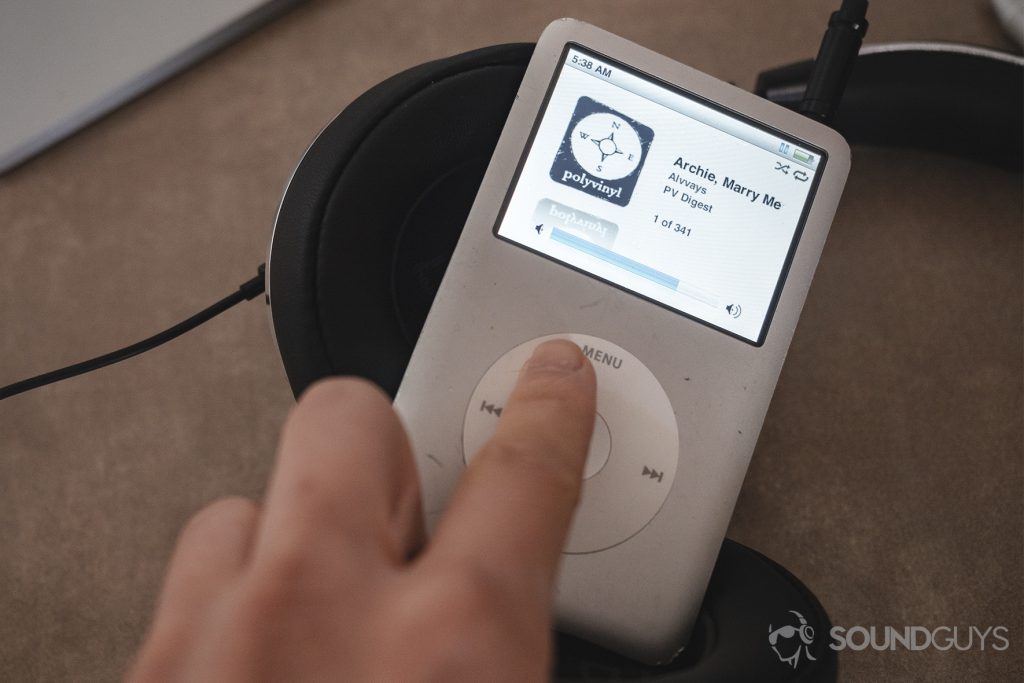

To meet the new demand for a way to listen to MP3 files, manufacturers started to release digital music players, capable of storing more music than the venerable compact disc in a package that was far more convenient. In 1998, the Recording Industry Association of America failed to win a judgement against Diamond for their MP3 player, thus opening the floodgates for more commercially-available portable music players. Now that there was no legal barrier anymore, any company could profit off of the explosive spread of the MP3.The decision was a rare double-whammy, as it were. On top of creating a legal market for MP3 players, it also set the precedent for a legal market for MP3 downloads in the following years, which also paved the way for the long-term success of streaming services. But there is one product that would help drive the final nail in the CD coffin. In October 2001, Apple released the iPod.

After the MP3 was done turning the music industry on its head, the MP3 Player came along and changed everything we know about smartphones.

To no one’s surprise, rival companies tried to ride on the Rio’s coattails, but hard drive players were still cumbersome and a chore to navigate. Things were slow. You could cook a frozen pizza, eat it, and return to your computer only to see that it was on the brink of overloading from transferring a few CD’s-worth of songs. As you may expect, this created a demand for a more efficient, portable, and intuitive music experience. It wasn’t until the iPod that gold was struck.

The rise of the iPod

Prior to October 2001, we recognized Apple for their computers and as that thing that magically keeps the doctor away. But Apple hit the ground running by announcing the iPod. Its debut form looks embarrassingly archaic from a 2018 perspective. However, at the time it was a breakthrough for portable music and carefully negotiated consumer demands for an all-in-one media player with an unheard of storage capacity of 5GB. Not only that, but the 1st gen iPod provided 20 minutes of shock protection. It’s comical now, but users could exercise freely without worrying about damaging the hard drive. Sure, it wasn’t the first compact MP3 player to reside in the pockets of children and women’s jeans alike, but it was the one that consumers unanimously drooled over.With the slogan, “1,000 songs in your pocket” and a well-timed release for the holiday season, the first iteration was a success, selling 125,000 units [3, 14]. Its spring 2002 update sealed the deal with Windows compatibility; users could easily operate within a well-oiled ecosystem unlike ever before. This provided a way to completely customize what music consumers bought, kept, and listened to without needing to carry a library of discs. Two years later, the 4th generation iPod received photo capabilities, foreshadowing the market for a multifunctional device.

A music player that takes photographs? What could possibly come next?As our voracious appetite for convenient media consumption grew, Apple and others continued to innovate, keeping up with the exponential curve of demand. Video playback and basic gaming functionality were integrated. Meanwhile, single devices were granted increasing functionality while becoming evermore portable. Of course, competitors garnered followers for their portable media players too, such as the Sansa Clip, which had dirt-cheap affordability on its side. But their efforts couldn’t keep pace with Apple’s iPod hierarchy.

Following the iPod Classic’s success, the iPod Mini had large shoes to fill. As we know, size six feet will never fill a size 10 shoe. Thus, Apple quickly rebranded the Mini in favor the Nano in 2005, which celebrated eight generations of success. This year also included the Shuffle, the “first iPod under $100” A summer later, Apple made a successful push to attract athletes with the Nike + iPod partnership. While Apple continued to roll out improved iPod iterations, they were also working on what was intellectually conceived in as “Project Purple” and “N45,” known to us lay-people as the iPhone and iPod Touch, respectively.

The king is dead. Long live the king.

Though we may never know if the chicken or the egg came first, we do know that the iPhone preceded the iPod Touch. The latter of which was a sleeker, thinner, sexier iPhone… without the phone, that is. Released in 2007, the Touch made for a costly holiday gift that year and for years to come. It served as a middle ground for parents uncomfortable with allowing their children unrestricted access to something like the LG enVAnnounced months earlier at MWC 2007, the iPhone made the buzz word. Passionate fanboys lead news outlets to refer to it as the “Jesus phone,” due to its cult-like following. The MP3 was now truly ubiquitous. We began to experience a decline in portable media player sales. Since having a separate device was too inconvenient for most people stopped using physical media in favor of their Swiss Army Knife of a smartphone.

Our phones shifted from a practical object to the extension of the self that we know today. Wherever we went and wherever we go, our music library follows. The iPhone release set the precedent for the next decade of smartphones. It allowed us to not only consolidate our devices but also to consolidate the control of our lives into a single apparatus. And to think, one of the first dominoes to fall was about a little diner on the corner of Broadway and 112th street.

Source: https://www.soundguys.com/podcast-the-mp3-revolution-17850/