Whereas the body’s annual Global Music Report focuses on revenues, this study is all about people’s music habits: how much they’re streaming and buying music; what devices they’re doing it on; and whether they’re still getting it from unlicensed sources at least some of the time.

The survey was conducted in April and May this year by the IFPI and its research partner AudienceNet. The 21 countries were: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, as well as China and India – although results from the latter two were not included in the IFPI’s ‘global’ figures in the report. Here are Music Ally’s 10 key takeaways from Music Listening 2019, which we’ve been reading overnight.

1. Surprise! Music-streaming is growing!

Okay, not really a surprise. On average, people are spending around 18 hours a week listening to music, up from 17.8 hours a year ago. It’s clear that streaming is driving this. 89% of respondents now use some kind of on-demand streaming service, while 64% listened to music through audio-streaming services in the last month. The latter stat is up from 57% a year ago.

2. It’s not just about the youngsters

This is a point that the IFPI stresses in the report. It’s true that

young people are the keenest streamers: 83% of 16-24 year-olds used

audio-streaming services in the last month, and 63% in the last day.

Meanwhile, 52% of them report having used paid streaming services in the

last month – the highest percentage for any age bracket.But the highest rate of growth for use of streaming services comes from 35-64 year-olds: 64% of 35-44 year-olds, 53% of 45-54 year-olds and 44% of 55-64 year-olds used audio-streaming services in the last month, up by nine, eight and nine percentage points respectively.

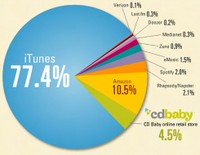

3. Video is the biggest music-streaming format

That ‘value gap’ argument about whether the music industry should be

getting more money from YouTube isn’t going away anytime soon. The

IFPI’s study claims that video accounts for 47% of on-demand streaming

consumption globally – remember, this doesn’t factor in YouTube-crazy

India – compared to 37% for paid audio streaming, and 15% for free audio

streaming.The IFPI also reckons that 77% of respondents used YouTube for music in the past month. That makes for an interesting comparison with YouTube’s own official figure, mind: in May 2018 it said that “more than one billion music fans come to YouTube each month”.

That said, video’s share of streaming is falling: in the IFPI’s 2018 study, 52% of global on-demand streaming time was video; 28% was paid audio streaming; and 20% was free audio streaming. So paid audio has taken a bite out of both the other categories over the last year.

4. Smartphones aren’t yet the biggest music device

There are some useful stats on ‘device share’ of music listening time

in the IFPI’s report. Radios are still the most popular device,

accounting for 29% of the time respondents spend listening to music.

However, smartphones are just behind, with a 27% share of listening time

– unchanged from the IFPI’s 2018 study.Of course, smartphones are bigger for younger listeners: they account for 44% off the time 16-24 year-olds spend listening to music, according to the study.

What about radio as a content form, rather than a device? The IFPI says that globally, music listeners average 5.4 hours a week listening to radio either live or on catch-up. That’s actually up by an hour year-on-year from the 4.4 hours reported in the 2018 study.

5. Smart speakers are gaining traction

Music-industry conferences love a panel session on how smart speakers

are The Hot Thing in music listening. But are they? The IFPI study

offers some numbers on that too. Globally, 20% of respondents have used

smart speakers for music in the last three months, although it’s as high

as 34% in the US and 30% in the UK.However, in the stats for device share of music-listening time, smart speakers are still niche: they only account for 3% of global listening according to the IFPI. That’s less than portable Bluetooth speakers (4%) and hi-fis / turntables (8%). That doesn’t mean smart speakers are a flop as a device category: it’s just some handy perspective for those excitable panels.

6. Pop is the tops… but younger people differ

It can feel like hip-hop and R&B are the dominant genres in the

streaming era, but from a global perspective, pop is still tops

according to the IFPI’s research. In fact, the top 10 favourite genres

globally are, in order: Pop; Rock; Oldies; Hip-hop / Rap; Dance /

Electronic; Indie / Alternative; K-Pop; R&B; and Classical.(Our assumption is that Indian film-music and Chinese C-Pop would be in the list if the IFPI was including the surveys from those two countries in its global figures.)

In the global list, ‘Oldies’ didn’t feature in the IFPI’s top-ten-genres list at all in 2018; hip-hop / rap has risen from fifth place to fourth; dance / electronic has fallen from third to fifth; and singer / songwriter has disappeared altogether –or possibly subsumed into other genres.

Again, younger listeners show different habits: 16-24 year-olds are more than four times likely to say hip-hop / rap is their favourite genre as any other age group. And not just American music either: 26% of French 16-24 year-olds cited French-language hip-hop as their favourite genre.

7. Music piracy has fallen in the last year

The IFPI has consistently campaigned against various forms of piracy,

and it’s not going to stop now just because legal streaming has pushed

infringement to the margins of the industry’s concerns. But its latest

study has some good news to bolster that trend.In 2019, 27% of respondents to its survey reported using copyright infringement as ‘a way to listen to or obtain music in the past month’. That’s down from 38% in last year’s study. 23% of respondents download music through ‘stream-ripping’ services, but that’s also down sharply – from 32% in 2018.

The IFPI maintains that piracy “remains a threat to the music ecosystem”, pointing to the 34% of 16-24 year-olds who stream-rip, but the overall trends feel positive.

8. Take a bow, Mexico

One of the stats that jumps out from the report is this: the 25.6

hours a week that Mexicans spend (on average) listening to music.

Impressive, compared to the 18 hours global average.It’s a reminder of why Mexico has become such an influential market in the streaming ecosystem, capable of propelling Latin American tracks into the global charts of services like Spotify. There aren’t just lots of Mexican music-streamers; they’re heavy listeners too.

(And that’s good news for rock bands: it’s the top genre in Mexico, ahead of pop and Latin pop.)

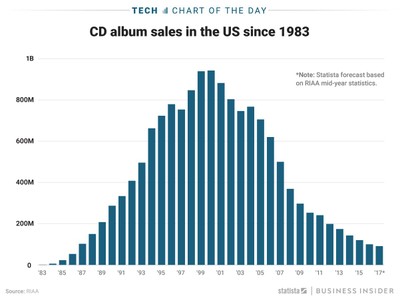

9. Koreans are the best at buying

When it comes to listening time, South Korea falls some way short of

Mexico, with an average of 13.9 hours a week. However, Koreans are still

tops when it comes to actually buying music: 44% of respondents there

said they’d bought CDs, vinyl or downloads in the last week, well ahead

of the 26% global average.Still, that average is a reminder that the modern music story isn’t entirely about streaming: more than a quarter of music listeners still buy, too.

10. Africa is still a mystery

The IFPI is upfront about its research methodology: for example the

exclusion of its India and China surveys from the global figures in its

new report. However, it’s important to understand what else isn’t

covered here.While the body notes that the 21 countries surveyed accounted for 92.6% of global recorded-music market revenues in 2018 as tracked in its Global Music Report earlier this year, like that report there’s only one country from Africa (South Africa) and none from the Middle East.

Africa, particularly, is a fascinating market for music listening / consumption, even if that’s not translating to meaningful (or at least easily-measurable) industry revenues yet. Music Ally would love to see someone tackle this issue with a continent-wide survey of similar scale to the IFPI’s new report.

Source: https://musically.com/2019/09/24/music-listening-2019-ifpi-report/